A peace of the action: Bernie Kennedy’s thought for the week

‘He showed a better way is possible.’

A Friend at our Meeting recently ministered about the word ‘meek’. It was contained in a quotation, part of a reading we had heard: ‘The humble, meek, merciful, just, pious and devout souls are everywhere of one religion; and when death has taken off the mask they will know one another, though the divers liveries they wear here makes them strangers’ (William Penn, 1693).

Our Friend wondered if the meaning of the word has changed over time. According to my dictionary, it means being ‘quiet and ready to do what other people say; amenable’. But it meant something quite different in biblical times. In Fingerprints of Fire, Footprints of Peace, Noel Moules coins the phrase ‘assertive meekness’. In the original Greek, he says, the word translated as ‘meek’ is praus. According to Moules, it consists of three aspects. Firstly, anger, specifically being able to express this emotion calmly, for maximum impact. Secondly, control, holding powerful forces in check. And thirdly, gentleness, moving with serenity and poise.

Moules cites the example of Jesus cracking a whip to clear out the temple. He was angry but he kept it under control. To be this meek takes guts, drawing on physical and mental strength. And it takes its toll.

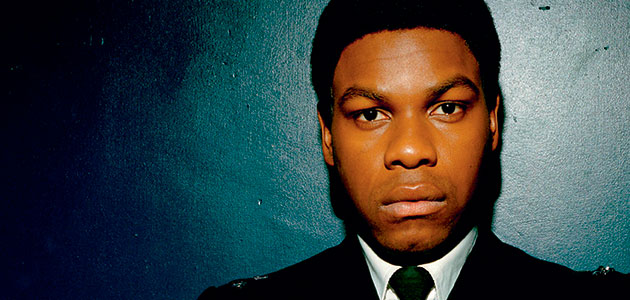

I wondered if there were any contemporary examples of assertive meekness. Anyone watching the recent Small Axe series on BBC1, showing the dreadful experiences of black Britons in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, would have encountered Leroy Logan. He was a young man in Hackney in London who became a research scientist. But he later decided to join the police force – to help, he says, his community, and to work towards change from within. He faces many acts of violence over thirty years of service. White colleagues ignore him, or stare at him. He is alone. Racist words are scrawled on his locker. This hurts. For some in his community, even in his own family, he is a traitor, a sell-out, a disgrace.

Such experiences can push you over the edge, even provoke you to use violence. Leroy Logan didn’t. He showed a better way is possible. After all, the police in the 1980s were hated and feared by large sections of society, regardless of race. And Logan made an important contribution to systemic reforms needed within the Metropolitan Police.

Moules contends that this kind of assertive meekness can lead to positive change in the face of injustice. Violence nearly always leads to more violence. In the end, people have to talk to each other – to make checks, laws, to enforce them and change practices and relationships at work and in wider society.

When our lives are over and we sit together, without our ‘divers liveries’, we will see.

You need to login to read subscriber-only content and/or comment on articles.