Finding a Quaker voice

Jackie Leach Scully considers bioethical consultations and the need for a Quaker input

Public consultations are all the rage. In the UK, canvassing public opinion is now an intrinsic part of the democratic process and the exercise of citizenship. At least, for certain types of legislation, we are regularly asked to express our opinion through a public consultation held by a government department or by a regulatory or advisory body on its behalf.

Ethical questions

Many of these consultations are so specific and, to the outsider, extremely technical that it is hard to imagine anyone not professionally involved having anything to say. But others are on broader issues, with more general implications for society and ethics. Some of the most high profile and contentious have been about bioethics: that is, directed at sophisticated developments in the life sciences and medicine that generate particularly problematic ethical and social questions.

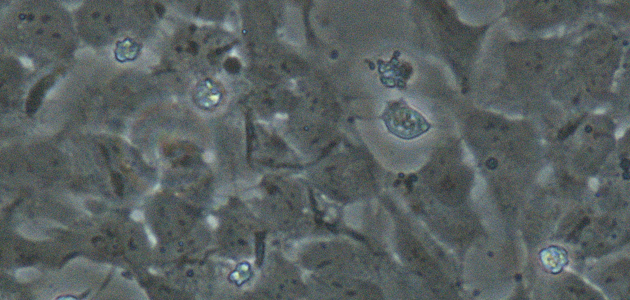

In 2007, for example, when the law on reproductive medicine and embryo research was being revised, the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) consulted on peoples’ responses to the idea of creating hybrid human and animal embryos for research that would be made possible by the proposed revision. Currently, the HFEA is again consulting public opinion on proposals to change the existing regulations to allow research on a new technique called mitochondrial donation or replacement. This research would, in principle, help avoid a particular kind of inherited disease.

Whose opinions?

As part of the Oversight Group formed by the HFEA to oversee the mitochondrial donation public consultation, and having been involved in some similar consultations, I’ve begun to notice whose opinions are routinely expressed here, and whose are not. Consultation responses are dominated by bodies with vested interests of one sort or another. Only a small number of individuals contribute their personal viewpoint or speak from experience. The vested interests include professional medical organisations, commercial companies and patient advocacy groups: if the issue concerns prenatal diagnosis or assisted suicide, there will be representation from right to life groups; if it has something to do with families or fertility, there will be submissions from groups that support particular views on the family or on the rights of parents or patients, and so on.

Of course, it is only right that people who feel the brunt of regulation should most want to influence it. However, the policy of a country isn’t solely about people who are directly affected. It also says something about the nation as a whole, about its identity and its moral life. So, public consultations hope to draw on the opinions of anyone who cares about the kind of society they live in, whether or not they have a personal involvement. Bodies like the HFEA would like to hear from more than just ‘the usual suspects’.

Quakers

My primary purpose here, however, is not necessarily to encourage individual Friends to go online and give their input to this or any other consultation – although I happen to think that would be a good thing. My concern is about the lack of input from the Religious Society of Friends. High on the list of usual suspects who have their say in public consultations are various religious bodies. Their responses are generally based on the official position of the faith group, and usually written by a theologian or someone similarly appointed to draw on the policy of the church, if it has one on the issue at hand, or if not to apply church teaching and provide a relevant interpretation. In practice, it seems that the clearer and more defined the church position, the more likely it is to make a formal submission.

A Quaker voice

In responses to a variety of bioethical consultations I’ve seen submissions from a range of faith groups, but not on behalf of the Religious Society of Friends. I think there are several reasons for this. One is structural. The way in which we arrive at corporate decisions (through individual discernment, before being brought before Meeting for Sufferings or Yearly Meeting in session) is very different from the process of appointing someone to compose a response on behalf of the church. Our way of doing things is, we hope, spiritually grounded in our distinctive theology and ecclesiology, but it doesn’t lend itself to joining in a consultation within a three-month timeframe.

It could also be that Friends don’t feel we have any unique input to make on, say, mitochondrial donation, as opposed to our stand on armed conflict or prisons. (If that’s the case, though, why should the Anglicans or the Methodists think they do?) It is true that the Religious Society of Friends in Britain tends not to have policies that are imposed on its members. The Catholic church would be able to state clearly that egg donation is against its teaching; by contrast, we might want to say something more like, ‘The approach of the Religious Society of Friends is less to determine whether or not egg donation is right or wrong, and more concerned with ensuring that Friends’ decisions reflect the fundamental principles of our testimonies and have been reached through a proper process of spiritual discernment.’

Friends might fear this sounds feeble in comparison with the robust statements of other churches, and wonder how saying it can be of any use (especially as we might end up saying something very similar, over and over again). But having been in the position of observing a regulatory body trying to use a public consultation to inform national policy, I’ve come to realise that it is helpful for policy makers to be reminded that not all ‘religious’ positions are the same or are arrived at in the same way. This is particularly necessary in contexts where religious viewpoints can be characterised (or caricatured) as homogeneous, authoritarian, and hopelessly detached from real-life experience?

Do Friends want there to be a way of ensuring that the Quaker voice is present in these increasingly important forms of civil deliberation? And if so, how?

You need to login to read subscriber-only content and/or comment on articles.